Previously, on As The Racial Micro-Aggressions Turn, our son was written up for inciting a brawl and, one year later, he was identified as gifted. He also was asked to bring to school a dish from our “home country,” so by the time our daughter had a similar assignment some years later, we didn’t bat an eyelash. Oh, you want her to wear native garb from our homeland?

We sent her in a cotton dress from Target. Don’t get me wrong. I am all in favor of celebrating ethnic diversity. But the emphasis on ancestral homelands strikes me as highly problematic for reasons that I can’t quite articulate. I turned to my mother for perspective. “Who keeps child-sized immigrant wear in their closet???” She refused to dignify the topic any further.

I also asked a few friends with school-aged children for their input. To make sure that my survey was scientific and unbiased, I made sure not to ask black people. My hypothetical question was pretty simple: what would you do if your kid was given an assignment to wear something from your homeland?

Orlando: “I would need to go to the second-hand store to find clothes I was rocking in the ’80s while [I was] residing in the international town of Tulare, CA.” Karen: “American Eagle suit; T-shirt with American flag on it; Red, white and blue flying suit; Women’s national Team USA jersey; Daisy Dukes.” Chandra: “I guess I could send him to school with some Irish beer.”

Clearly, these friends are not very authentic, so I consulted my pal, Marilyn, reared by a family of educators in the Midwest and one of the most socially aware people that I know. She also has not one but two African American children. Surely, she must have her finger on the pulse of diversity education in schools.

Marilyn: “USA! USA! Or we could dress her as a hick.”

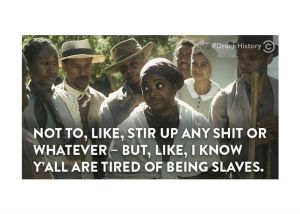

She then went on to explain how her friends let their children dress up in the traditional wear of a country that they are interested in, rather than sticking to the whole Dress Like Your Ancestors assignment. Hold up, I say. You mean this is an actual assignment for the school? I thought we were speaking in hypotheticals for the purpose of this research. “Yes,” Educated Marilyn texts back. “Every year [my daughter’s] school celebrates Multicultural Day and encourages all of the students to dress in their native garb. There is a parade during recess and all of the parents are invited.” Then Marilyn has a revelation. “Maybe they can dress as Harriet Tubman.”  I realize now that this topic requires greater reflection. WHY do schools think these assignments are a good idea? What assumptions are being made about people’s histories and culture? On the one hand, black American kids or other groups who don’t readily identify as immigrants can feel marginalized during these school-sanctioned celebrations, particularly when there is an emphasis on “home” being outside of the U.S. Additionally, we run the risk of constantly viewing some groups (e.g., Latinos) only through an immigration lens, as though they are perpetual visitors and outsiders. Just as important: with all of the emphasis on clothing and food, what messages are we sending to young people about multiculturalism and cultural sensitivity?

I realize now that this topic requires greater reflection. WHY do schools think these assignments are a good idea? What assumptions are being made about people’s histories and culture? On the one hand, black American kids or other groups who don’t readily identify as immigrants can feel marginalized during these school-sanctioned celebrations, particularly when there is an emphasis on “home” being outside of the U.S. Additionally, we run the risk of constantly viewing some groups (e.g., Latinos) only through an immigration lens, as though they are perpetual visitors and outsiders. Just as important: with all of the emphasis on clothing and food, what messages are we sending to young people about multiculturalism and cultural sensitivity?